The Value of Art in the Age of Generative AI

Published:

"To see something as art requires something the eye cannot descry—an atmosphere of artistic theory, a knowledge of the history of art."

— Arthur Danto

Why do we find certain works of art valuable? The usual answers (beauty, originality, emotional impact) are true, but incomplete. Beneath them lies a quieter mechanism, one that often operates unconsciously. When I look at an artwork, I imagine myself in the place of its creator and ask a simple question: what if I had to make this? How much effort would it take? How many years of training, how many failed attempts, how many deliberate choices?

We value art by running the thought experiment of creating it ourselves. This is not about the artist’s actual labor, but about perceived difficulty. Value emerges from a counterfactual simulation of how costly it would have been for me to produce. There is a second ingredient: art feels valuable when it seems unlikely, when it feels like something that could not easily have existed. Given the tools and resources available, what is the probability that this particular artifact would come into being? This probability depends critically on the tools available at the time of creation. Some pieces hang in museums because they were unexpected and hard to produce a thousand years ago, when the available tools were primitive. The same piece, if made a hundred years ago with more advanced tools, would carry far less artistic value. Value comes, in short, from how hard it feels to make and how unlikely it seems to exist given the technological context of its creation.

These intuitions can be made explicit in a rough model of artistic value. Let $A$ denote an artwork, $T$ the available toolset (paintbrushes, cameras, or AI models), $L$ the perceived labor or effort if human-made, and $N_T$ the expected number of artworks producible by $T$.

The model has two components:

[V(A) = \lambda f(L) + \mu \big[-\log P(A \mid T) - \log N_T\big]]

The Effort Component: $f(L)$ captures how we value perceived difficulty. This resonates with labor theory (Marx, 1867), but it is fundamentally subjective: a cognitive simulation of the creator experience, rather than actual labor cost (Kant, 1790). When we encounter an artwork, we mentally reconstruct the steps required to produce it: the years of training, the failed attempts, the deliberate choices. The function $f$ might scale as $L^\alpha$ for some $\alpha$, reflecting how human valuation responds to perceived complexity and mastery. This counterfactual effort estimation is what gives art its perceived value, independent of the artist’s actual labor.

The Rarity Component: $-\log P(A \mid T) - \log N_T$ borrows from information theory, but connects more deeply to algorithmic information theory. The term $-\log P(A \mid T)$ measures creative surprise: how improbable the artwork is given the tools. In algorithmic complexity terms, this relates to Kolmogorov complexity. Low-probability outputs, those requiring high complexity to generate given the model, stand out as surprising and thus valuable. But this is diminished by $-\log N_T$, which accounts for the abundance of possible outputs. When everyone can generate endless art, uniqueness is lost. This is what Walter Benjamin called the aura: that quality of uniqueness and embeddedness in time that diminishes when reproduction becomes trivial (Benjamin, 1935). Even if technique or content is aesthetically compelling, the aura collapses when the space of possible outputs becomes effectively infinite.

Here is where AI infrastructure investment matters. Consider the massive capital poured into training models: data centers, compute clusters, engineering teams, and energy costs. This investment $I_T$ is amortized across all possible outputs. If a toolset can produce $N_T$ artworks, the per-artifact infrastructure cost approaches $I_T / N_T$. For generative AI, $N_T$ is effectively infinite, since the model can produce countless variations. As $N_T \to \infty$, the amortized cost per artifact $\to 0$, and $-\log N_T \to -\infty$, driving the rarity component toward negative infinity.

This framework brings rigor to artistic valuation through counterfactual effort and generative rarity. Philosophical accounts acknowledge that artistic value isn’t reducible to monetary or labor inputs. They involve aesthetic, moral, and expressive dimensions. But by formalizing the cognitive mechanisms of valuation, we can see why certain works feel valuable and others do not. The framework explains much of traditional art valuation, but it breaks when confronted with generative AI. The perceived effort collapses to near zero (often just a prompt), and the rarity term collapses as $N_T$ becomes effectively infinite.

Generative models undermine both pillars of value. The perceived effort is minimal, often no more than a prompt, and the rarity evaporates as the space of possible outputs grows effectively infinite. From this perspective, AI-generated art appears destined for near-zero value, and yet this conclusion feels wrong. Not all art that looks simple is worthless.

Simplicity With History vs. Simplicity Without

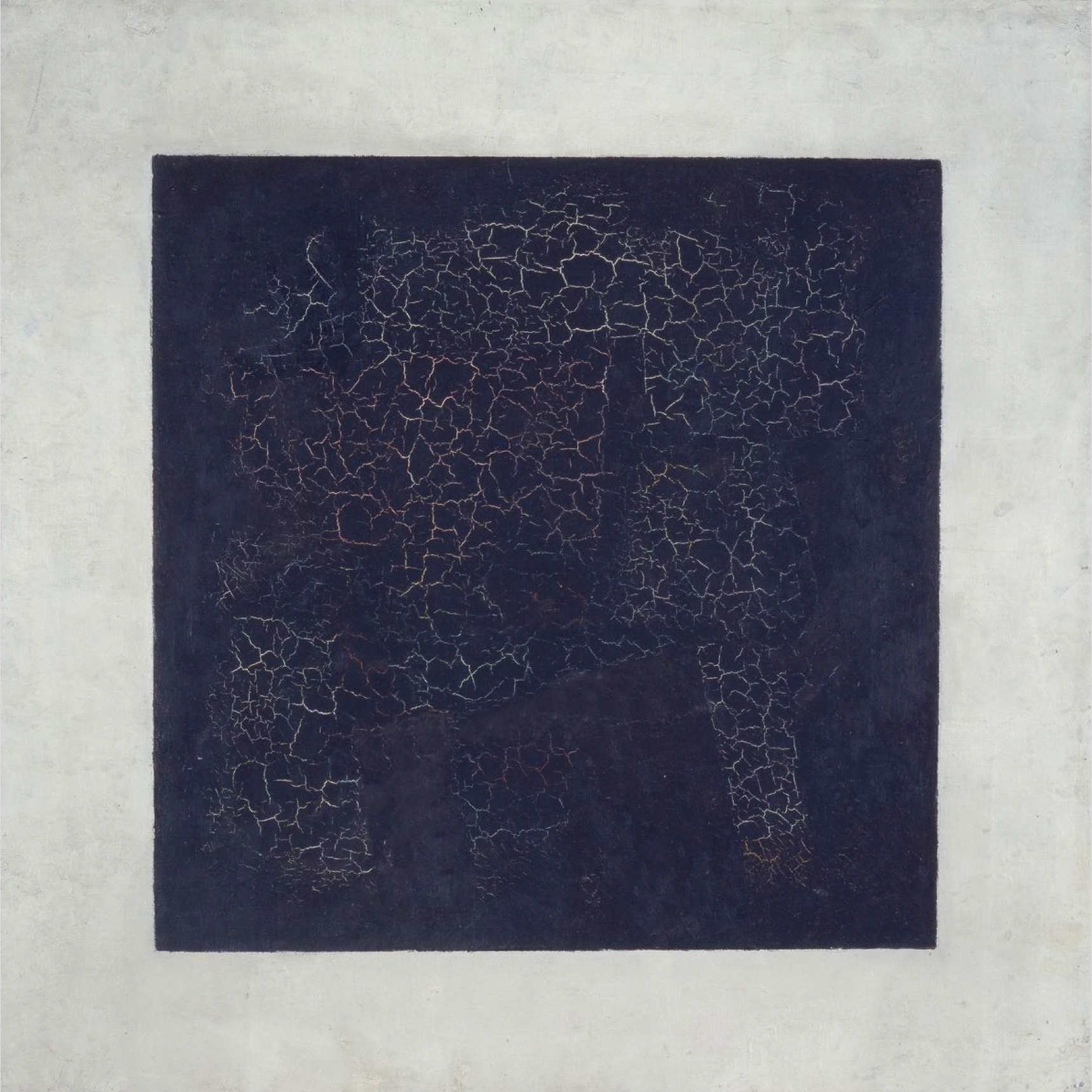

Consider Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square or Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain. These works are almost trivial in execution. Anyone could paint a square or place a urinal in a gallery, yet their value is immense.

Kazimir Malevich, Black Square, 1915 | Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917 |

Why are these works so valuable? Because their simplicity is backed by history. They carry biography, rebellion, institutional confrontation, and cultural rupture; they changed the trajectory of art itself. Their value lies not in effort or visual complexity, but in their aura: their embeddedness in time, society, and meaning.

An AI-generated image, no matter how visually impressive, usually lacks this trajectory. It appears fully formed, without struggle, intention, or rebellion. To capture this missing dimension, the value model must be augmented:

[V(A) = \lambda f(L) + \mu \big[-\log P(A \mid T) - \log N_T\big] + \nu H]

Here, $H$ represents historical and societal weight: narrative, institutional recognition, cultural impact, and accumulated meaning. Human minimalist art may have low $L$ but high $H$, while AI-generated art typically has both low.

A Case Where AI Art Gains Value

Still, AI-generated art can have value, just not in the traditional sense.

Imagine a teenager experimenting with a generative model late at night, typing:

A dog solemnly pondering a chessboard, painted in the style of Caravaggio.

Generated by GPT-5.2

They post the image online without much thought. Somehow, it resonates. People remix it. It becomes a meme, appearing on protest signs, profile pictures, and T-shirts. For a brief moment, it captures a collective mood.

In this case, the value of the image does not come from the effort of its creation, nor from its rarity or artistic mastery. It comes from what happens after. The artifact becomes a vehicle for coordination, expression, and shared meaning. Its value lies not in the object itself, but in its ability to be taken up by people and embedded into action, discourse, and collective identity.

The artwork functions less like a finished piece and more like a catalyst. Its significance emerges through reuse, reinterpretation, and circulation. What matters is not who created it or how difficult it was to make, but whether it becomes part of a broader social movement, whether it is adopted, repurposed, and woven into human activity.

This is a fundamentally different kind of value: retrospective and relational rather than intrinsic. The artifact does not carry meaning on its own. Meaning accretes through human response.

"The meaning of a work of art is not exhausted by the moment of its creation."

— Hans-Georg Gadamer

The artifact itself is cheap, but the meaning is not. This kind of value, however, is fragile and fleeting. Generative AI does not produce occasional oddities. It produces everything, all the time. When novelty becomes continuous, disruption becomes rare. When everything is possible at once, almost nothing feels disruptive. If Duchamp’s Fountain appeared today, amid billions of absurd AI-generated provocations, would it still shock? Or would it simply disappear into the noise? This is the paradox of AI art: its infinite productivity may erode the very conditions required for cultural rupture.

A New Kind of Value We Cannot Yet See

Yet it would be premature to conclude that AI art is valueless. It may be that AI will create an entirely new kind of artistic value, one that does not resemble painting, sculpture, or even memes. Perhaps human-made art will become boilerplate, much like hand-written code once did, and the higher level of art may lie in orchestration: designing and connecting vast, complex structures of meaning that remain difficult even for AI to reproduce.

The deeper risk is that our brains may not yet be ready to perceive such value. Throughout history, artistic appreciation evolved alongside human cognition; our capacity for abstraction, symbolism, and interpretation grew gradually. AI’s generative abilities, however, are advancing far faster than our perceptual and conceptual frameworks. It may already be producing artifacts of potential value that we cannot yet recognize as art. When creation itself is cheap and infinite, value must be rediscovered elsewhere.

AI-generated art does not fit comfortably into our existing value systems. It lacks effort, rarity, and historical depth, though it can still acquire value through human attention, memes, and narratives. But these are fragile, easily saturated, and unlikely to reshape culture at scale. The deeper question is not whether AI art has value today, but whether it is pointing toward a form of value we have not yet learned how to see. Art has never been just about objects; it has always been about the human stories wrapped around them. AI simply reveals this truth more starkly by showing us what art looks like when the story is missing.

References:

- Benjamin, W. (1935). The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Available online

- Kant, I. (1790). Critique of Judgment. Available online

- Marx, K. (1867). Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume I. Available online

"The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes."

— Marcel Proust